Contact

PO Box 2397

Virden Manitoba

R0M 2C0

ManitobaOilMuseum@gmail.com

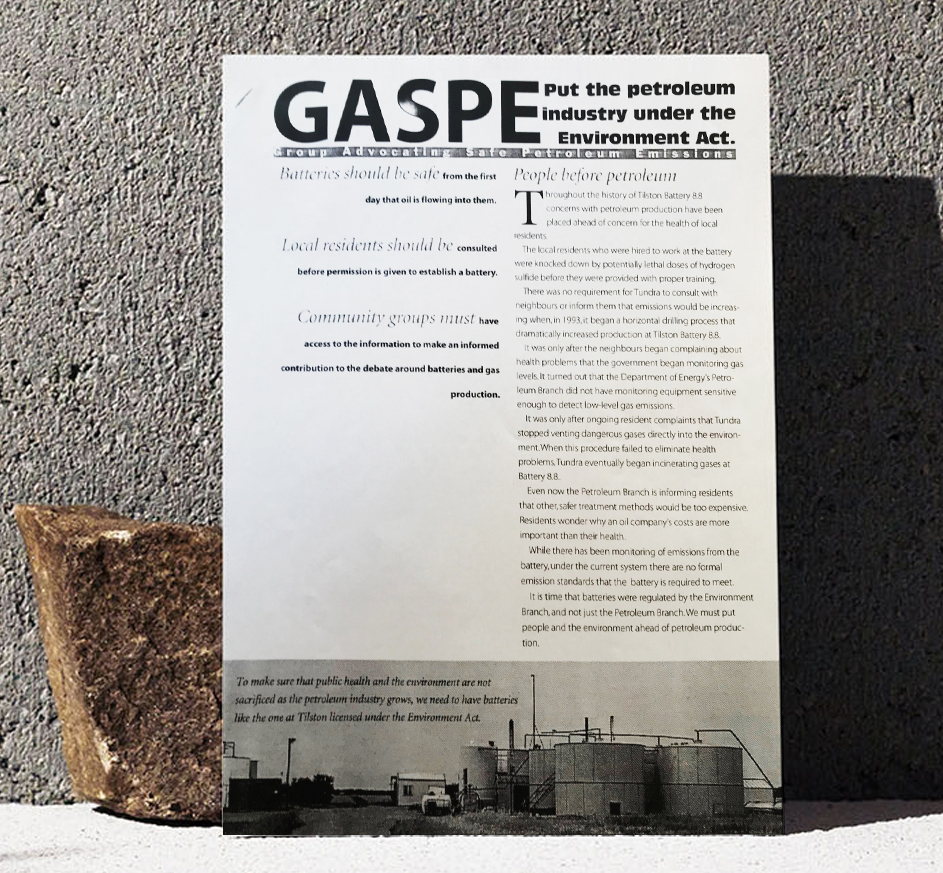

Group Advocating For Safe Petroleum Emissions

Preface

This story is based on field work regarding Bill 21 the Amendment to the Oil and Gas Act in Manitoba 2005 that was repealed in 2019. This work was conducted during the course of a PHD program at the University of Manitoba. The final dissertation is available online here. The story is a culmination of interviews, data collected from other sources and analysis. The participants are given code names to keep their identities annoymous and the quotes have been slightly modified for simplicity The photo gallery at the end is a very small example of documents collected and archived by the GASPE group during their operations.

Synopsis

The acronym G.A.S.P.E. (Group Advocating for Safe Petroleum Emissions) was the first indication of a group that a PHD student had found on a legislative Hansard from the year 2005 in relation to Bill 21 The Amendment to the Oil & Gas Act[1]. The student had been trying to understand a webpage on the Manitoba Petroleum Branch website that referred to an issue with “Air Quality”[2] and Tilston, Manitoba. During the search the student had found Bill 21 (The Amendment to the Oil and Gas Act) and, eventually, a group of concerned citizens who had lobbied in 2005 for the amendment. It took some time but the student connected with the key members whose names were on the 2005 document and she arrived to a small farmhouse in southwestern Manitoba for a group interview around a kitchen table. This was a group of neighbours whose experiences of oil in Manitoba had catalyzed them to act and also brought them together so closely that they could finish each other’s sentences. In the space of three hours they cried, laughed and shared their memories and stories with the student as recounted below.

The Creation of GASPE

We thought the government would look after us (Participant CBEND 1920). We did. We thought that the oil industry would look after us. You know, would not do anything that’s going to harm anybody (Participant AWEND 1920).

That was the frustrating thing. I was so naïve I thought, we would go tell our story and everyone would believe us, and we’d get something done (Participant AJEND 1920).

The interview started off with sorrow, some tears and a statement of betrayal. AW warned me, “I was going to say, this is going to be tough for CB and CL” (Participant AWEND 1920). She was referring to two of the members around the table, a couple whose parent was instrumental in linking the H2S gas from the battery site to the sickness being experienced by their cattle and their bodies. This was also the couple that made a tough decision to move themselves and their cattle away from home after their eldest son was knocked unconscious by the gas. The decision to move came about after a slow process of putting things together: the information about the effects of H2S experienced by people elsewhere in Canada and the USA and the couple’s actual everyday experiences. AW explained, “Took a while to get some of us on board because, you know, it was kind of bizarre… so there was a kind of a period of time in there, years actually, before we all caught on. But then it was like, ok” (Participant AWEND 1920). The ‘ok’ moment for CB and CL occurred after a couple years where they struggled with weakened cattle, with higher-than-average miscarriages in the herd, and with regular sickness in their family. “The year we moved away from home, our kids…we just had two living at home then….and our doctor visits went from 43 to 13” said CL. “In a year?” I asked. “Yes…and our kids were always on antibiotics” she told me (Participant CLEND 1920).

The context for these realizations occurred during a time in Canada and the USA where information about H2S gas was increasing and becoming more of what Li (2015)[3] describes as a “matter of concern” to populations, where there is a perception of instability and communities are catalyzed into action due to the contestation of the facts. One participant I spoke to pointed to mobilization of communities around large-scale hog farms in rural Manitoba in the late 1990’s (Participant KLE0819). These large-scale hog farms were sites where large amounts of H2S were produced and could travel. According to my participant, municipalities were catalyzed to push back on provincial changes in regulation that would allow these farms to be set up in a few different places across Manitoba (Participant KLE0819). This was also during a time when some activists in Alberta (such as Weibo Ludwig and Jessica Ernst) were receiving attention for their actions to contest fracking operations. The author Andrew[4] Nikiforuk has written books detailing the story of both of these people who struggled in many ways to draw attention to the process of multi-stage horizontal well hydraulic fracturing as a matter of public health concern. Weibo Ludwig was an activist in Alberta who become frustrated by the activities of oil and gas extraction around his home and took action starting in 1996 to destroy oil company property, including the bombing of a Suncor site[5]. Ludwig became a pivotal figure in the constatation of oil and gas in Canada, particularly fracking of sour gas wells. Jessica Ernst’s story is of a legal battle where she sued a company for contaminating the aquifer during fracking operations and later also the regulatory body of the Alberta provincial government for withholding information that would help her make a case (in particular baseline data on her water well). Ernst was a landowner and rancher who also did work for oil companies but eventually quit in protest and over concerns that she could light the water from her water well on fire due to contamination, she said, was caused by fracking practices nearby. Her battle and her work to advocate and share her story widely has, in fact, caused other jurisdictions to place bans or moratoria on fracking practices, however in her own case she has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars and recently had her whole case dismissed by the Supreme Court[6]. Essentially has been unable to hold the company or the government to account for their actions that caused considerable health concerns for herself, her neighbours and the animals on her ranch. So, the GASPE group was influenced in various ways by these activists in Alberta and, relating their experiences to the lived experiences of these people, learning better ways to organize but also seeking to distance themselves from appearing or being such radical activists.

So, in the late 1990’s, the group was small but linked together by their shared experiences living with and learning about H2S in their environment. The reasons they arrived at the creation of a non-for-profit organization called GASPE were varied. There were the immediate, sensory experiences. AJ told about two different times when he was knocked unconscious by the gas while working for an oil company at the battery. The first time he treated it like a silly accident, and his wife, a nurse at the local clinic did the same. The second time, however, he almost died.

AJ: That day I opened the hatch to the tank and, I don’t know what happened after that. My brother was at the battery and he came up and I was laying up in the catwalk… [later at home] …I got out of the truck at home and walked in the house, and down I went again, he said. Just, I went over again. And he says, they took me to the hospital. Second time, it was different… (Participant AJEND 1920).

As an oil worker at the battery with his brother, he also remembers clearing dead birds off the top of the tank, “...and virtually every morning you’d throw about 5 or 6 dead birds off” (Participant AJEND 1920). In fact, it was the experiences of the animals, in particular the cattle, that really convinced him and a couple of the others. There were more instances of miscarriages, deformed calves, and they wouldn’t put on weight, “CB just kept saying, ‘What am I doing wrong?’” (Participant AJEND 1920). However, the clincher for AW was the connection between her body and the monitor at their neighbour’s house.

AW: I was skeptical, I need to have a little bit of proof or something. I mean you can’t just say you are having a heart attack because you got a pain in your chest, eh? Something has to tell us that. That was, I guess, my thinking and he took me up to his house and his monitor was being silly [reading higher H2S levels]. It was really being silly, and my head always seemed to be able to tell me when there was nonsense going on and, instantly I was like. Oh, shit there is something in this house (claps hand down on the table). If he hadn’t have done that I would have probably still been wandering around in a fog, in a daze thinking well you know, I guess this [being sick] is how it is (AWEND 1920).

This connection between information about H2S, the readings from an H2S monitor and the feelings experienced in her body that had become sadly familiar to AW, was enough to convince her of the gravity of the situation. She uses the phrases, ‘being silly’ and ‘nonsense’ to indicate moments when the device would be reading higher than safe parts per million amounts of H2S gas in the air while her body also felt out-of-sorts, unwell, or strange to her. The use of these words also gestures to the continued lived experience that, in effect, did not make sense even while receiving evidence that it was in fact a reality.

The group spoke to the H2S experiences where they began to learn the topography of the area from the way the wind usually blew to the areas or slumps of land where the gas would settle. They would map the conditions and correlate them to their own bodily conditions, becoming, as they would say, their own detectors. This was a valuable practice, which they would use to begin a paper trail of complaints to the local government office of the Petroleum Branch. The four people around the table and others around them who were part of the network, when they were in the vicinity of the battery site, would call in complaints, “if you ever thought you were getting gassed” (Participant AWEND 1920). It was important to know how H2S made your body feel and to be able to connect the feelings with where you were at the time. Once these neighbors began to do this, their experiences of H2S gas solidified into a certainty that became unshakeable. Even today they know when they are experiencing H2S gas leaking from a battery or a trunk containing oil, water and gas from a well site.

The weight of evidence, of their experiences, of the H2S detection device, of the animals, convinced these neighbors and so they formed a group and began to try and advocate for some changes to the battery site. However, they needed a guide, which is where WW stepped in. He was a local reeve but also a friend, living nearby but not in the vicinity of oil wells or batteries. He describes being convinced by AW: “I figured that there was something wrong when AW lost that little gleam in her eye” (Participant WWEND 1920). WW had experience and connections within the local government and had an understanding about how to get one’s voice heard in government. “He was our savior” said CL quickly joined by AW agreeing, “Yeah, he found us an avenue” (Participants CLEND 1920). It was WW who suggested creating an official non-profit group, which they cleverly named G.A.S.P.E. or Group Advocating for Safe Petroleum Emissions.

AW: [We made it a non-profit] to make us seem more serious. That was a suggestion and [the Public Interest Law Firm representing the group] agreed. If you are an actual organization then you’re much more credible to the public, perhaps. And it did, it served a very (agreement around the table), yeah. I think it did it. It was good. (Participant AW END 1920)

The organizational status gave the concerns a public face and some credibility, in terms of being an entity the government would come to deal with as a group. This acronym also made them easier to find and identify in my internet searches. This organizational status also gave them a purpose and something to work towards; safe emissions. Moreover, it communicated to those who were skeptical that they were not against oil and gas extraction; “CL: So, we are not against the oil industry, we were (CB: Advocating) advocating (AW: for safe) for safe petroleum emissions” (Participants END 1920). This was essential for two reasons: 1. The Manitoba Surface Rights Association could not help them because the Surface Rights Act only applies to concerns with the land, and gases or air quality do not fall under that legislation, and 2. People who organize around oil and gas are often labeled as being against oil and gas in its entirety and sometimes, in one particularly egregious example, seen as terrorists (such as the examples of Jessica Ernst or Wiebo Ludwig).

The Actions of GASPE

Once the group had come together and each member had been convinced of the need to act, act they did. The timing of each of these actions was a bit unclear, having happened almost 20 years ago in the late 90s and early 2000s, so I begin the story with the establishment of the legal non-profit Group Advocating for Safe Petroleum Emissions (GASPE). The group had been working on gathering a paper trail of complaints by those in the group and anyone else in the area of the battery. The strategy was to gather evidence for the regulating body and industry in order to show that there was a problem with H2S gas leaking from the nearby battery site. The industry already knew there was H2S gas that occurred in the shale oil field and this was apparent due to the fact that AJ and his brother, who worked for the oil industry, were required to carry H2S monitors. It was an aspect of workplace safety. However, AJ says,

AJ: Yeah, but when we worked there though, like 10 parts per million, [was the official amount declared as unsafe] …Like all the alarms they go off. Well, we had them hanging in our truck and they’d go off on the road, before we went in the battery. So, our supervisor at that time, he got them turned up to 15 parts per million, which we really shouldn’t even have been working [in those conditions] (Participant AJEND 1920).

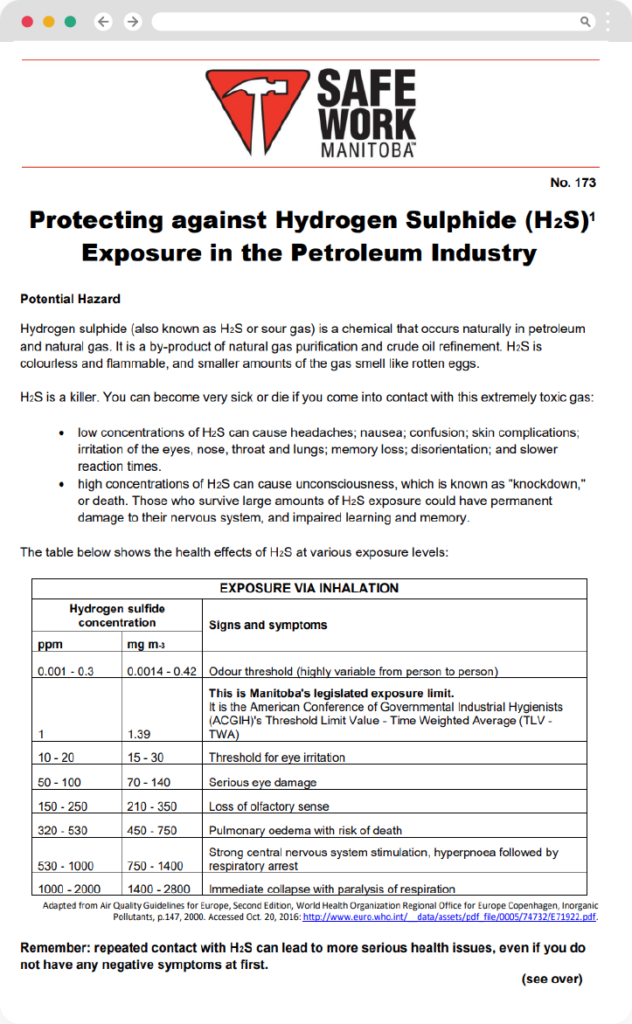

There are well-documented hazards of H2S gas and clear safety guidelines, as seen in this image (see Fig. 18) taken from a Safe Work Manitoba Bulletin[7]. This bulletin lists the parts per million (ppm) limit that would trigger an alarm, while also listing the symptoms at different levels. However, in the late 1990’s the threshold limits were higher (10-15ppm) and, according to my participants, enforcement of these guidelines were much less strict. The group also attempted to gather evidence that the gas traveled further than expected by industry and also maintained higher than safe parts per million at locations such as the homes of nearby inhabitants. H2S does not remain in the body in a way that can be tested, so a person experiencing the effects of H2S gas must be their own witness to the effects of the gas. The inability to test for H2S exposure created a situation where the evidence of H2S exposure put forth by the group and others in the area, who sent complaints to the Manitoba Petroleum Branch and the company, was questioned and undermined as being inaccurate. The inaccuracy of the information was based on previous studies and data collected by industry and government that suggested people living near to battery sites should not experience H2S, which was contrary to the findings of the GASPE group. The industry and the government, drawing on information held by the government on the acceptable levels of H2S, were thus able to dismiss most of the concerns of GASPE, even while making some changes to the practices of the battery to attempt to reduce the amount of H2S leaking from the site. The company who owned the battery site changed a few things at the battery site; putting a fence around the battery with a sign declaring, “Do not enter, Poisonous Gas Area” (Participant WWEND 1920) and later installing a higher stack (the chimney that allows the gas to escape), and installing an incinerator to burn the gasses more thoroughly before they were released into the air. Yet, this was only, as WW put it, “To get one step ahead of us, they put that big stack up. (AJ: Yep) And made a big issue about that, about how many 100 thousand dollars they spent on the battery (general agreement)” (Participants END 1920). The contradiction at work here is that the concerns of the people in the area were acknowledged by the fact that the company made material efforts to limit the amount of H2S coming from the battery site, however at the same the people in the area were also made to feel as though the company also made a ‘big issue’ about how much money they spent trying to make it safer. The group felt as though they had been placated and were supposed to stop complaining due to the efforts of the company, however, they were still experiencing the negative effects of the H2S gas leaking.

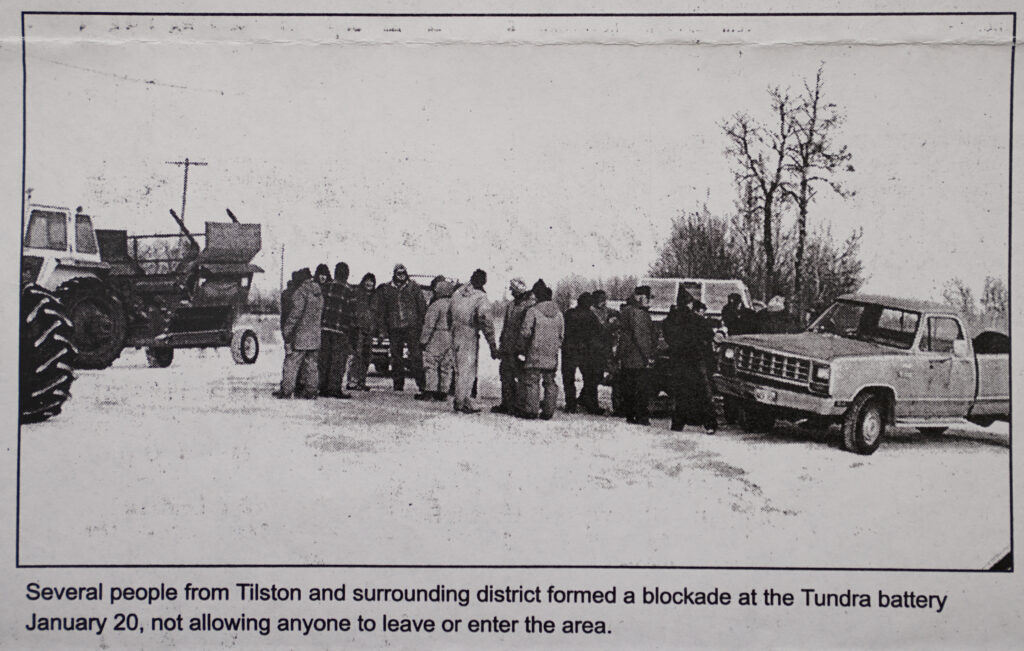

However, one thing did occur definitely as a result of industry reactions to this series of complaints. The group became fed up with the delay tactics and lack of acknowledgement. On their last day of work, AJ and his brother who had quit the oil company, staged a blockade at the battery site;

AJ: It was my brother and I operating but we quit and the last day we quit, we decided to, we may as well [do something]. I guess that was it. So, we ordered a truck in and then blocked. And you and [CB]I took our tractors over and blocked the road, just to try and get someone to listen to us. It was frustration (AW: Plain and simple) (Participants END 1920).

The blockade was supported by their neighbours; “Our local community backed us (Agreement around the table)” said AJ. It was in 2000 or 2001 they said, and it was out of, “absolute frustration. We ended up, we just left them there [speaking of the blockade] until we had some [company officials] and some government guys there and, yeah.” (Participant AJ END 1920). After that confrontational episode, the government took interest and word got out in the media about GASPE and what they were attempting to do. It was because of this notoriety that they started receiving support from all over the province/country, anonymous letters and phone calls from people sharing similar stories.

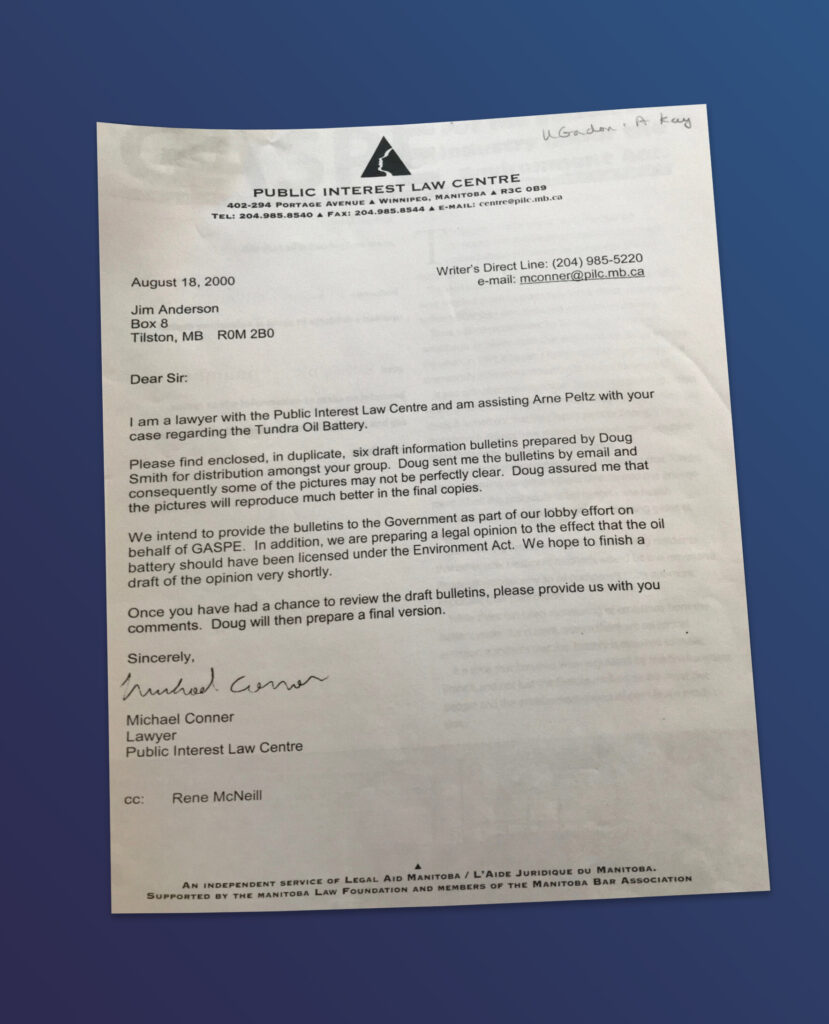

GASPE also worked with the Public Interest Law Centre in Winnipeg to collect a Statement of Facts for a lawsuit. They pulled together their families’ health records and any other information to try and link the poor health of their bodies and their animals to the H2S gasses leaking from the battery site. In tandem with these efforts, they had enough government officials on board to get an amendment to the Oil and Gas Act drafted and placed before the Standing Committee on Social and Economic Development on May 3rd, 2005[8]. They gave testimony before this committee, recorded in a Hansard transcript of the legislative proceedings, to argue for why an amendment was needed and what it would do for them. The main components of Bill 21, the Amendment, would reclassify battery sites to a different “class” or type of development that would trigger a full environmental assessment as well as an arms-length, third party public inquiry board that would be responsible for hearing community complaints and organizing on their behalf. In transcripts of that evening of May 3, 2005, there is agreement by GASPE members as well as the oil industry that the Manitoba Petroleum Branch was similar to the “fox guarding the henhouse”[9]. There was an obvious conflict of interest that the Amendment would attempt to correct.

Responses to GASPE’s Activities

Many of their activities did catalyze responses from the government and industry, however, it was an uphill battle at every turn, even after gaining support and media coverage. The group described continuous instances of frustration, such as having someone in a government position actually listen to them and then, a short time later, that person would be moved to a different job within the government. Indeed, most of their experiences recount instances where they were denied, delayed and ignored. This is very much in line with other academic research that details the difficulties oil and gas communities have in voicing concerns, being heard, and having the situation change.[10]

On the Manitoba Petroleum Branch’s website there is a section titled, “Air Quality,” which takes you to another webpage where you can access two reports from 2000-2001 on air quality around Tilston, MB[11]. These air quality studies appear to be a direct result of the complaints and blockade of the GASPE members. However, the studies were only done in the vicinity of Tilston, Manitoba, even though there were battery sites across the southwestern corner and the GASPE members were directly involved in this study.

CL: They set up the monitors at Bill’s and you [referring to AJ and AW’s farm], and WW was the monitor police (WW: Yep)

AW: Yeah, they let WW be the monitor police, the doors were locked (laughter around the table). So that we couldn’t tamper with it.

CL: And they set up a health study, which didn’t prove anything. It said, um,

CB: Too small a sample.

CL: Too small a sample. The symptoms were [in line with H2S exposure but] it couldn’t be proven, because it was too small a sample (Participants END 1920).

The study concluded that there was not enough evidence to indicate that the amount of H2S is a hazard to those living near to the battery site[12]. However, it did suggest that the industry needed to take measures to ensure that H2S was not allowed to accumulate to become hazardous. There were never any other government studies done in southwestern Manitoba. However, the company that owned the battery site, also hired someone to come out and conduct their own study of the battery.

AW: [The company] hired Entec (agreement around the table) to come out and do a study. Says that yep, things at the battery were working efficiently.

AJ: Was that the Entec guy, they sat up all night and he got sick? He couldn’t work the next day because his head, because he had such a headache.

CB: Yeah (Laughter around the table) (Participants END 1920).

Again, contrary perhaps to the direct experience of the technician, their experiences were denied as not containing valid proof of the existence of high enough levels of H2S to cause the concerns they were alleging. One story indicates the exasperation particularly CL felt regarding this continued denial of their experiences.

CL: We would occasionally go over to [The oil company’s] office and go and see [the director] and ah, we were into this, I don’t know how many years and, he said one day, “you don’t know how hard this is on me!” (laughter around the table). The four of us were sitting there and, our usually calm and docile CL, (laughter).

AJ: Palms come down on that table, the whole table bounced about two or three inches off the floor. He knew you were serious then though. (CL: I don’t know) He changed his tune after (Participants END 1920).

Earlier in our conversation they told me that the CEO of this oil company told them that he was sorry, but he couldn’t compensate them for their trouble because if he did with them, he would have to with every group that complained to them. Yet, they also, laughingly, told me that their complaining resulted in many other people in the area receiving more money from the oil company than they would have otherwise. They called this “hush money.”

The lawsuit against the oil company, which the Public Interest Law Firm was involved with, provides another series of stories about the group’s evidence being discounted. They gathered a Statement of Facts with all their health information and that of their cattle, but in the end most of the evidence was discounted. It was seen as ‘hearsay’ and taken from the official record. As three of the group recounted to me:

CL: They just kept whittling away so that there was nothing. (AW: yeah). It just basically said our names and,

AJ: Too small a group to take on a multi-millionaire. Like they are just too rich, we can’t. (AW: Yeah) And delay it, eh? They just (AW: Oh, they delayed it). Like how many times, they would, we would get close and then they’d switch lawyers. (Yep, and other agreements around the table).

AJ: And we start all again. And it was to their benefit. Eventually, like, they got the oil patch dry (Participants END 1920).

The group told me they went before a judge twice but nothing came of it because the case would be delayed due to formalities, and then, they ended up with a lawyer from the Public Interest Law Firm who was unsympathetic to their story and this upset them enough to make them quit trying. Also, as noted by AJ, the battery was closed and so their immediate concerns dissipated along with the leaking gas. They told me, in many ways, how they had to move on with their lives.

As they moved on with their lives, the legislative work they did to try and amend the Oil and Gas act to change the classification of battery sites and also to develop an arm’s length inquiry panel for hearing and dealing with complaints did not move on. As I mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, it was this work that led me to GASPE through the legislative transcription, or record of the committee meeting where Bill 21, The Amendment to the Oil and Gas Act, was discussed and later approved. However, even though it was written into a bill and could be found on the Manitoba Government website as a legislative document (The Oil and Gas Amendment and Oil and Gas Production Tax Amendment Act, C.C.S.M., once assented to, c 034) and on the Manitoba Petroleum Branch under “Acts and Regulations,” I determined that it had never been implemented. When I spoke to the Petroleum Branch and the interim director about this, I got this drawn-out response:

MO: And the reason why it wasn’t proclaimed; so the act at the time was introduced, but it didn’t become law because it wasn’t proclaimed, the reason it wasn’t proclaimed is because there are a lot of regulations associated with it. So, I have got my (takes out a large binder), like this is all our acts and regulations and so, the oil and gas act have… (flipping through the binder) Sorry, it has all my things, but you know we’ve got one, like the production drilling regulation. There is a royalty incentive regulation associated with it so, there’s a bunch of regulations that come under it. So, in order to make some of those changes that were in there we had to do regulatory changes first. So a lot of the time the process that might happen when there is an act with regulations. Like there are certain things in the act that a regulatory change has to happen, which is different. Which is a different process it goes through Cabinet. So, the act gets introduced in the house and then, if it’s passed, but if there are regulations associated with it to make it, [difficult], to kind of put it into practice. Because the regulations end up being more detailed. That is something that gets put through a Cabinet process. So, it goes public in the fact that there is comment on regulations but, the, it doesn’t get voted on by the house, it is the Cabinet that decides. So, I can’t say why those regulations were never done but that is the reason it wasn’t proclaimed because the regulations, there were quite a few regulations that had to happen and somewhere along the line, and I don’t know why, it didn’t get done. And I don’t know if it was, if it was intentional. Like if there was something politically, they changed their mind on, or if it was more of a case of the staff resources just didn’t get it done and it kind of got [put to the side] but obviously, there wasn’t a lot of push for it to happen. And so now we’ve got a situation where it's 18 years old, and there is a new government (Participant MO0628).

In other words, it didn’t happen because it was too complicated and there was not actually a lot of interest in making it happen and now, it will not happen at all[13]. The way this was explained to me, as witnessed by the rambling way this quote tries to explains, is indicative of the way responsibility is diffused so thoroughly that it cannot arrive at any one spatial (or temporal) location. When I talked to the GASPE group about the fact the amendment had not passed, they were not surprised but didn’t know about it.

AJ: I think, I sort of doubted it [the Amendment] ever would [be implemented] though. The industry is just too powerful. And I think they can run our government. (laughs)

CL: Well, they do. Well, ok I am maybe a bit biased there. It seems to me as though they do. Is that better? (laughs) (Participants END 1920).

After they gave testimony, they had started to let it all go and move on with their lives as best as they could, which was easier due to the closing of the well sites and battery.

AJ: I think that they, they wore us out though.

AW and WW: Yeah, they did.

AW: And we had to move on, we (agreement around the table).

CB Yeah. It consumed our lives and life is too short.

WW: It consumed your life for too long it was, and they played that game. They knew damn well what they were doing.

CL: It was very smart of them. And that was their purpose (Participants END 1920).

Yet, there were lasting effects, one family never moved back and they suffer from increased sensitivity, memory loss, and other ailments that have been linked to long term low dose exposure to H2S[14]. Also, as mentioned above, Bill 21 the Amendment to the Oil and Gas Act that would have minimally changed oil & gas operations by including an environmental assessment in the creation of battery facilities (where oil, gas and water are separated) and by creating a separate body for hearing community company, was repealed in 2019. Currently, there is no required environmental or community assessment in the creation of any oil and gas infrastructure, beyond what is deemed necessary by the Manitoba Petroleum Branch (who can consult at their own discretion).

GASPE Gallery

References Footnotes

Manitoba Government (2005, May 31). Third Session - Thirty-Eighth Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba Standing Committee on Social and Economic Development. (ISSN 1708-6698). Manitoba. Retrieved from http://www.gov.mb.ca/legislature/hansard/38th_3rd/hansardpdf/sed1.pdf

Manitoba Government. (2001, Jan 11). “Health and Air Quality in Tilston, Manitoba.” Retrieved from https://www.gov.mb.ca/health/publichealth/tilston.html.

Li, F. (2015). Unearthing Conflict: corporate mining, activism, and expertise in Peru. Durham: Duke University Press.

Nikiforuk, A. (2014). Saboteurs: Wiebo Ludwig's war against big oil. Vancouver: Greystone Books.

Nikiforuk, A. (2015). Slick water: fracking and one insider's stand against the world's most powerful industry. Vancouver: Greystone Books.

Nikiforuk, A. (2014). Saboteurs: Wiebo Ludwig's war against big oil. Vancouver: Greystone Books.

Nikiforuk, A. (2021, May 18, May 18, 2021). The Brutal Legal Odyssey of Jessica Ernst Comes to an End. The Tyee. Retrieved from https://thetyee.ca/News/2021/05/18/Brutal-Legal-Odyssey-Jessica-ErnstEnds/

Safe Work Manitoba. (2016). Protecting against H2S Exposure in the petroleum industry. Retrieved from https://www.safemanitoba.com/Page%20Related%20Documents/resources/BL173_HydrogenS phideExposurePetroleumIndustry_16SWMB.pdf

Manitoba Government (2005, May 31). Third Session - Thirty-Eighth Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba Standing Committee on Social and Economic Development. (ISSN 1708-6698). Manitoba. Retrieved from http://www.gov.mb.ca/legislature/hansard/38th_3rd/hansardpdf/sed1.pdf

Manitoba Government (2005, May 31). Third Session - Thirty-Eighth Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba Standing Committee on Social and Economic Development. (ISSN 1708-6698). Manitoba. Retrieved from http://www.gov.mb.ca/legislature/hansard/38th_3rd/hansardpdf/sed1.pdf

(see for example these following references)

Eaton, E., & Kinchy, A. (2016). Quiet voices in the fracking debate: Ambivalence, nonmobilization, and individual action in two extractive communities (Saskatchewan and Pennsylvania). Energy Research & Social Science, 20, 22-30.

Malivel, G. (2019). Addressing Community Exposure to Hydrogen Sulfide in the Saskatchewan Oilpatch: Interdisciplinary Investigations as a Lever to Expose Industrial Risk. Master’s Thesis.York University, Toronto.

Willow, A. J. (2016). Wells and well-being: neoliberalism and holistic sustainability in the shale energy debate. Local Environment, 21(6), 768-788.

Wylie, S. A. (2018). Fractivism: Corporate Bodies and Chemical Bonds: Duke University Press.

Wylie, S., Wilder, E., Vera, L., Thomas, D., & McLaughlin, M. (2017). Materializing Exposure: Developing an Indexical Method to Visualize Health Hazards Related to Fossil Fuel Extraction. Engaging Science Technology Soc, 3, 426-463. doi:10.17351/ests2017.123

Manitoba Government. (2001, Jan 11). “Health and Air Quality in Tilston, Manitoba.” Retrieved from https://www.gov.mb.ca/health/publichealth/tilston.html.

Kraut, A. (2000, Nov 20). Health Assessment of Residents Residing Near Oil Batteries in the Tilston, Manitoba Area. Retrieved from Manitoba Government: https://www.gov.mb.ca/health/publichealth/docs/tilston.pdf

It was repealed in 2019 by the The Reducing Red Tape and Improving Services Act, S.M. 2019, c. 11.

Safe Work Manitoba. (2016). Protecting against H2S Exposure in the petroleum industry. Retrieved from https://www.safemanitoba.com/Page%20Related%20Documents/resources/BL173_HydrogenS phideExposurePetroleumIndustry_16SWMB.pdf

Ecojustice. (2017, Nov 8). Letter to Julie Thompson Re: Canada Gazette, Part I, September 9, 2017 — Draft Screening Assessment re Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S), Sodium Sulfide (Na(SH)) and Sodium Sulfide (Na2S) (“Draft Screening Assessment”).